Material transformation

Most people do not make sculpture. Okay, our art school training has taught us to question even that assertion because what, really, constitutes a piece of sculpture? Or an act of sculpture (for those of you inclined to privilege the verb over the noun in such a description)? But tantalizing tangents aside, we mean this at face value: most of our readers neither make, nor often think much about, sculptural works of art. When pushed, many are likely to think of marble, bronze, or clay when considering sculpture par excellence, and perhaps the occasional steel (stainless or otherwise). Please understand, we don’t mean this in any derogatory way. Instead, it underscores the rewards and hazards of specialization in education as well as the challenges of making and exhibiting contemporary three-dimensional art.

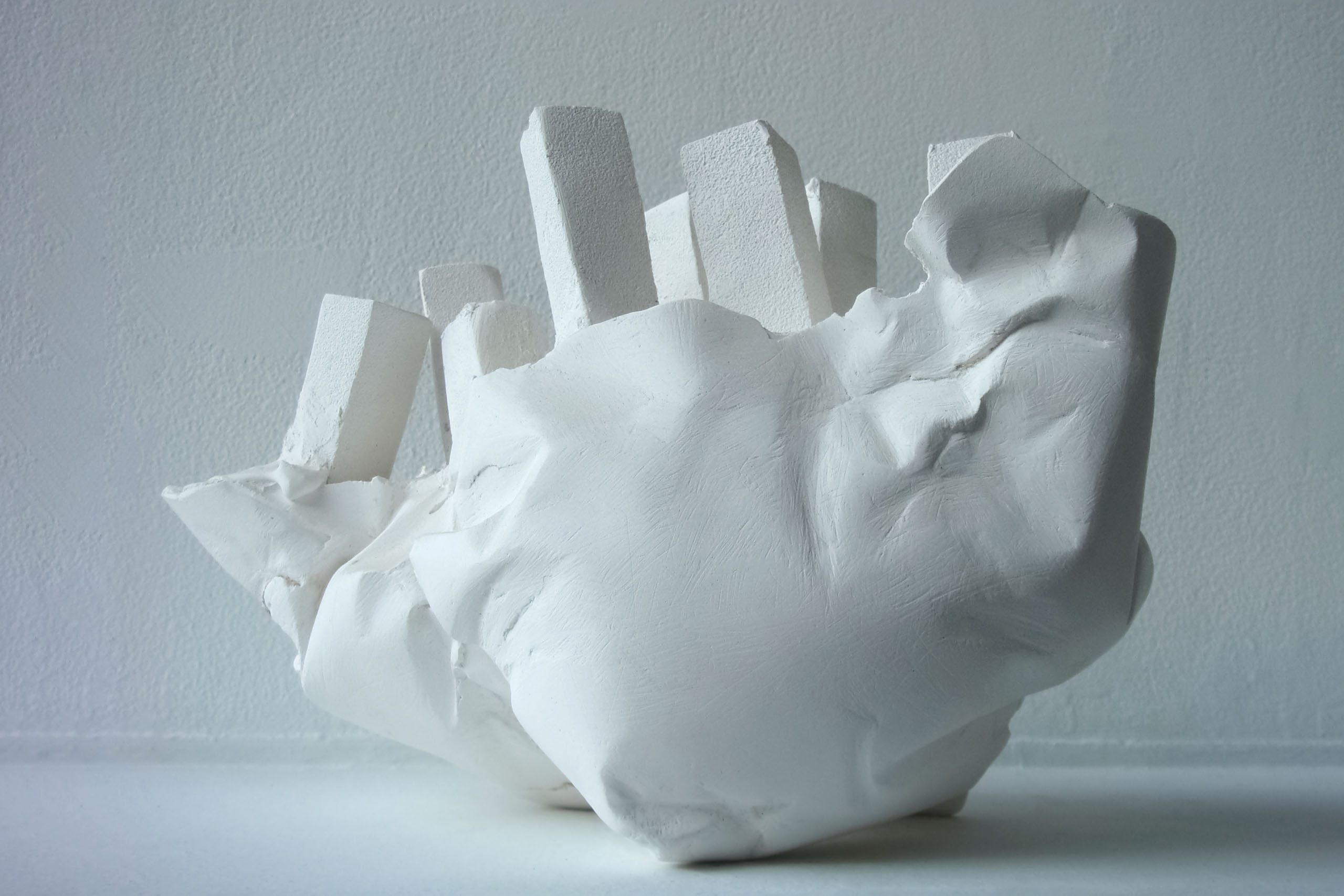

As a budding sculpture student in many fine art programs, you are likely to take some sort of course on ‘materials and processes’ which introduces you to an array of traditional and current ways of taking raw material and transforming it into a finished artistic product (we’ll set aside considerations here of art, craft, and industrial design for want of space and endless tangents). Think woodshop, plaster, metal casting, perhaps construction or fabrication lab technologies. This particular unit of instruction is all about the aforementioned ‘material transformation’ by means of which a raw chunk of something joins with idea and varying level of skill to become something other, something more. The fundamental act of creation, of making something.

Postmodern principles and contemporary practice

Well. Then comes the rub. Any first semester art student will rattle you off a list of design principles — while we discuss these elsewhere, you may be familiar with terms such as repetition, variety, movement, balance, and so forth. Assimilating this knowledge can be very useful, certainly in understanding that which has preceded us but also in practicing our own craft. However…Olivia Gude either changed (or named the change critical to) contemporary practice with her ‘Postmodern Principles’ — appropriation, juxtaposition, recontextualization, layering, interaction of text and image, hybridity, gazing, and representation. Couple this with her ‘Principles of Possibility’ and hopefully you’ll come to appreciate why serious art education is not for the faint of heart.

As always, we’re aware of that tiny voice in your head now asking, “okay, so what can this tell me about business?” Thank you for bearing with us. The point: it is not enough to learn how to build. In the words of Seth Godin (perhaps mis-applied, but we’re running with it) — “Making is insufficient.” We cannot pretend that it is 1900 and seek to imitate the process of Rodin (or Carl Milles, if you’d like a Swedish sculptor dear to our heart). Today it is as viable a solution to find the elements of a sculpture as it is to make them, as respected to assemble as it is to construct. The beauty in this is the recognition in so much of the world around us of that which is already worthy of our attention — that seeing the inherent qualities of a piece of stone (or even consumer plastic) negates the requirement to re-shape it into something other. At the same time, the prerequisite of technical skill loses a bit of its edge: yes, knowing how to take a slab of clay and shape it into a vessel is powerful, but so too is the nuanced understanding of form that takes 1000 multiples of an object and finds a compelling outcome. What a strange and wonderful world we inhabit.

All things are not equal, but these are rich and challenging considerations when you next encounter a piece of sculpture (again, not to mention the incredible legacy of contemporary design that toys endlessly with the relationship of form and function). In such moments, ask yourself whether the outcome before you has been built, found, assembled, or some combination of these (or other inflections thereof). Meaning accumulates in unruly ways, which is much the point we’d now like to discuss as it pertains to branding.

What we talk about when we talk about branding

People use all sorts of ways to describe what a brand is (or means or does — even here things become slippery). As with most ideas (and the words that represent them) the second you start to look closely, you find yourself in surprisingly murky water surprisingly fast. Did you catch that? We slipped into metaphor to make a point that might feel abstract, far more concrete and, therefore, understandable. Language around branding does this in spades…fun, isn’t it? Working as educators taught us endless lessons — many of which we’ll share here over time — not the least of which was the centrality of metaphor to learning, and human understanding at large. Metaphor allows us to use something familiar as a way to frame, and therefore assimilate, new information. It enables us to see and think differently.

When you start listening for it, you’ll hear people (ourselves included) describe branding by all manner of equivalencies: a brand is a promise, a brand is an idea, a brand is the result of everything a company does, a brand is the feeling someone has when they think of your business. What’s interesting about this way of thinking is that all of these are likely to be true (or at least serve as effective pathways toward the truth) as is one of our favorite ways of considering branding — as a fantasy. In his book Brand Seduction: How Neuroscience can Help Marketers Build Memorable Brands, Daryl Weber uses the idea of the “brand fantasy” persuasively, to describe the loose (and messy) associations “of fleeting images, abstract thoughts, and nuanced emotions that, for the most part, live below our conscious awareness.” Weber tells us that all of this comes together to form a ‘brand fantasy’ — an aspirational representation of something “people want to have, something they want to be associated with and connected to, or provide a taste of the life they’d like to live.”1

We like this way of thinking because it resonates with our own interpretation of how we (and others) move through the world — as consciously and carefully as we’re able, but inevitably inconsistently and full of contradictions. As rational beings who enjoy thinking and analysis, it’s no small blow to our sense of self to admit that as fallible humans, we still operate as much by feeling as anyone else — as susceptible to the seductions of a brand as the rest, even as we think about their construction regularly. So a primarily semantic question in sculpture becomes a central problem in brand building: are they built, found, or assembled?

Some conditional conclusions

Unsurprisingly, marketers and designers often focus on the parts of brand development over which we have control. This not only makes sense, it’s also a crucial part of establishing a strategic foundation. There is so much outside our circle of control, and often any hope we have of nudging something across this boundary begins with giving it a name. You want to communicate more effectively so folks will buy what you have to offer? It really helps to know clearly and with nuance the person receiving those messages. The tone, feel, and visual elements that will be persuasive? Oh so critical to identify them thoughtfully. Hopefully even these snippets of the strategic process illustrate the point: this much can be analyzed and rationally developed, this much can be built. It is likely transparent at this point (but we never tire of stating the obvious) that the actual living, breathing humans with all their likes and dislikes, memories and desires constitute that part of branding which is found. Certainly we are all changing, changeable individuals, but our feelings can also be oddly resilient and irrationally stubborn.

To bring things back to our initial foray into sculptural practice, consider that even the most direct form of a found object installation necessitates at least one action from the artist: selection. In order for a piece to even register as art to others, an artist must point to the object identified, offering context by repositioning it to the space of the gallery, taking a photograph, or at least notating the selection in a written statement. In much the same way, as we work to build a brand it is not enough to merely find, unless we engage with that which is found. People bring all of their inner complexity and assumptions and associations to our shared cultural products, and ultimately a brand results from the aggregation of all this richness, individually and collectively.

This, then, would be our conditional conclusion: a work of sculpture can be built, found, assembled, or any mix you desire of these and other approaches. In the case of branding, the outcome is always necessarily an assemblage of some which is built and much which is found. Keep this in mind as you undertake the exciting (and hopefully rigorous) process of your own branding efforts. Be as thorough and conscious as possible around the proverbial white board, but give equal measure to the irrational and unconscious and messy nature of feelings we find out there in the real world. Respecting the found shapes how you think about the built, and greatly improve the odds for success in that which you assemble.

1 Weber, Daryl. Brand Seduction: How Neuroscience can Help Marketers Build Memorable Brands, Career Press, Wayne, NJ, 2016, pp. 14–15.